by Jenny Künkel

In order to investigate the attitudes and demands of homeless activist groups, researchers of the PostdocLab working group ‘Urban Conflicts and Property’ conducted a workshop with homeless activists from different German cities. Among other aspects, the activists criticise the capitalist logic of the housing market and see homelessness as a structural problem.

The cross-university working group ‘Urban Conflicts and Property’, funded by the College’s PostdocLab Programme, analyses the contestations of property in urban space. The team consisting of Philipp Kadelke, Nina Schuster (both TU Dortmund University) and Jenny Künkel (University of Duisburg-Essen) explores topics beyond the trodden pathways of real estate financialisation, rent protests and gentrification research. Under a common conflict-theoretical framework, the research group studies the practices and political opinions of private small-scale landlords (Kadelke), conflicts surrounding allotments (Schuster), and how social work organisations assume or assist the role of property owners who rent and manage apartments to homeless people in “housing first” programmes (Künkel). In doing so, the researchers also take the perspective of the affected people into account – i.e., renters, gardeners and, not least, the arguably most precarious group, the homeless.

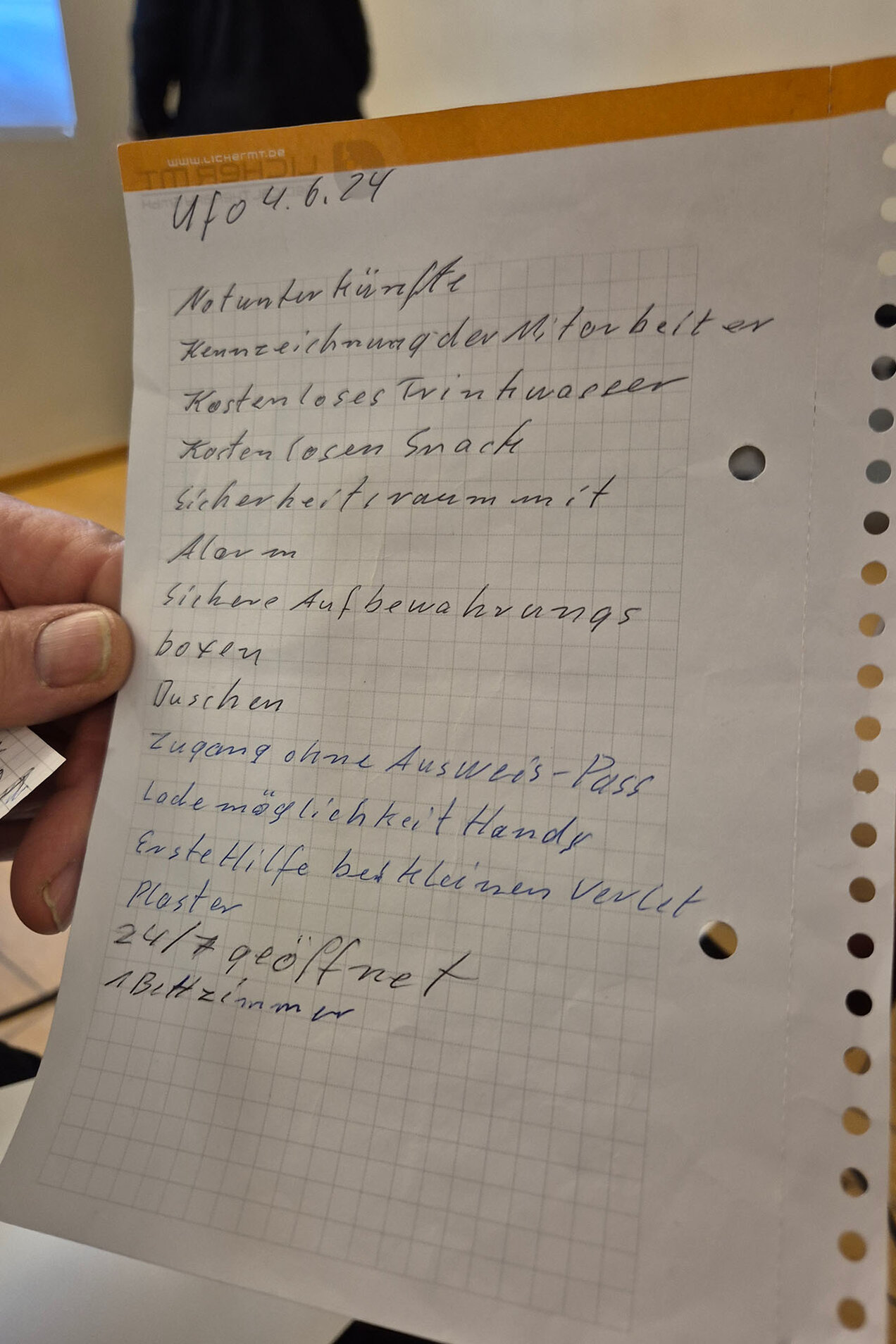

As one of the first empirical components of the project, the group conducted a workshop with 15 homelessness activists in Berlin in December 2024 – among the participants were two co-organisers from Wohnungslosenstiftung Berlin and 13 activists from different German cities who had been homeless in the past or who are currently living on the street or in shelters. The objective of the workshop was to investigate homeless people’s needs, so it focussed in three steps on 1) main problems for people without housing, 2) potential solutions and 3) concrete strategies to get there. At the same time, this approach allowed for examining the participants’ problem framings, theoretically drawing on the insights of discursive policy analysis that focusses on the ways in which aspects of life become a public problem or not (e.g., Bacchi 2019).

The workshop was facilitated by a very engaged group of discussants. The activists were happy to use the event for their nationwide networking and, more generally, considered it to be a booster to their activism. Homelessness activism had already been on the rise before the workshop, since homelessness became more visible and urgent in the context of multiple crises (e.g., the Covid pandemic, shifting migration patterns, and an accelerated housing crisis in times of inflation and rising energy prices). The numerous unmet demands in the social system that currently contribute to exclusions of migrants and mentally ill people and promote a deprofessionalisation of social work are unlikely to disappear in the near future (Sowa et al. 2024). Yet, due to an EU initiative, and considering the rising numbers of people without housing in Germany, the government at the time acknowledged homelessness in the 2021 coalition contract, proclaiming to end it by 2030, and lanced a (contested) project of counting homeless people in 2022 (Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales 2022).

Though somewhat plausible against this background, the activists’ happiness at the workshop – promoted by the provision of food and not least the wonderful soups the Wohnungslosenstiftung had cooked – was quite unexpected. Homelessness activism is anything but common. As has often been pointed out (e.g., Nagel 2023), homeless people are unlikely to form stable and successful movements due to a multiple lack of resources (e.g., money, space, time, influential allies, links to formal politics, and often also political experience). Also, the base from which homeless movements can recruit their members is ever more diverse (ibid.). It comprises not only youth fleeing the violent institution of the family but also a very heterogeneous group of adults, including mentally ill people and an increasing group of refugees and EU labour migrants that are discriminated against on the housing market and, due to more restrictive social and migration policies, are increasingly excluded from the German welfare state (Atzemüller 2022). All these people are occupied with very existential problems in their lives that leave little time for organising.

Yet, not only did the Covid pandemic enhance the public perception of street scenes and their needs (e.g., Künkel 2020), and homeless activists relaunched their wide networking (e.g., forming the Selbstvertretung wohnungsloser Menschen e.V.). What is more, rent protests that have gained momentum since the mid-2000s, especially in Berlin, made a conscious effort to create links between different social problems and heterogeneous social groups (cf. Bach/Berfelde 2024). This included reaching out to homeless people by visiting their outdoor homes and villages, discussing housing problems and organising the joint squatting of a residential building in Berlin in 2020 (Valentina/Jose 2022).

©

Jenny Künkel

©

Jenny Künkel

Against this background, it is less surprising that activists were not only strongly empowered (“infecting” the PostdocLab researchers with their high spirits) but also proved to be highly informed about housing policy: For example, they questioned property vacancies fostered by tax law, the alleviation of lawsuits for personal use, and forced evictions, especially from buildings in public property (on further demands of the homeless see: Künkel 2025). The specific political background also partially explains why the activists consistently framed homelessness as a structural (environmental justice) problem that can only be resolved by the provision of housing and requires the questioning of private property.

Unlike other highly marginalised and criminalised groups, such as sex workers or drug consumers, whose protests have often invoked liberal anti-discrimination, self-determination or ideal-victim frameworks (e.g., Künkel 2021), the homelessness activist discourse repeatedly pointed to an underlying capitalist market logic. While this meant casting aside some of the more immediate problems such as a lack of security on the streets (where, in the activists’ views, people should not be forced to live in the first place) or possible needs for psychological care, it set a non-individualistic focus on other issues. Both the frequent interpersonal conflicts in homeless’ lives (e.g., with shelter staff or other homeless in crowded shelters or the streets) as well as the degrading conditions in public shelters (e.g., severe lack of hygiene, crowded bunk-bed accommodation and stressed-out staff) were explained by the competitive logics of capitalism. Especially mass shelters for temporary accommodation were seen to be a business model in the housing market which yields high profits. Similar criticism was raised regarding some of the projects operating under the unprotected label “housing first” (which, in its ideal conception, provides long-term individual housing unconditionally rather than placing homeless people in different forms of shared accommodation first to assess their housing competences and treat addictions or mental problems; cf. Güntner/Harner 2021).

Beyond the anti-capitalist framing, similar to the anti-discrimination discourse of other street scene movements, stigma was a recurrent topic. The homeless compared their situation with having to live, all of a sudden, completely naked for years. It was particularly in these discussions about stigma that within-group differentiations were evoked. Activists felt the need for social distinction from drug consumers, as they experienced an equation of drug consumption and homelessness as the most common prejudice. However, discrimination against other homeless was constrained by the structural framing: The discussants agreed that such distinctions “should not matter” and that homelessness is “never an individual problem.” Thus, in consequence they stressed that all homeless should stand together (e.g., across ethnic groups) in their struggle for justice or at least a safe roof over one’s head.

Given this inspiring solidarity (and the fact that the activists happened to constantly invoke the key topic of the research group, private property, which came in very handy for the research), the workshop provided a fantastic start for the team of the PostdocLab working group ‘Urban Conflicts and Property’.

Jenny Künkel is a postdoctoral researcher and lecturer at the Institute of Social Work and Social Policy of the University of Duisburg-Essen. She graduated in human geography from Frankfurt University and has worked as postdoctoral researcher at the renowned Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique in Bordeaux (France) and as substitute professor in urban geography at the University of Dresden. Her research focus is on conflicts and marginalisation, especially in the context of neoliberalisation. Her work includes studies on sex work, drug consumption, policing, precarious migration, and social movements.

Atzmüller, Roland (2022): ‘Renationalisierung der Sozialpolitik’, in: Betzelt, Sigrid / Fehmel, Thilo (Eds.): Deformation oder Transformation?. Wiesbaden: Springer VS. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-658-35210-3_2 (accessed: 11.04.2025)

Bacchi, Carol L. (2019): ‘Introducing the “What’s the Problem Represented to be?” Approach’, in: Tröndle, Martin / Steigerwald, Claudia (Eds.): Anthologie Kulturpolitik: Einführende Beiträge zu Geschichte, Funktionen und Diskursen der Kulturpolitikforschung. Bielefeld: transcript, pp. 427–430.

Bach, Nina / Berfelde, Rabea (2024): ‘Mietenpolitik – hartnäckiger Kampf um eine breite Basis’, in: Bescherer, Peter / Griesi, Elettra / Künkel, Jenny / Mackenroth, Giesela (Eds., 2024): Der Bewegungsraum der sozialen Frage: Wo Protest Platz hat und Raum findet. Münster: Westfälisches Dampfboot, pp. 88–96.

Bundesministerium für Arbeit und Soziales (2022): ‘Erstmals belastbare Zahlen über Wohnungslosigkeit in Deutschland’. https://www.bmas.de/DE/Soziales/erstmals-belastbare-zahlen-ueber-wohnungslosigkeit-in-deutschland.html (accessed: 11.04.2025)

Güntner, Simon / Harner, Roswitha (2021): ‘Wohnen, Wohnungslosigkeit und Wohnungslosenhilfe’, in: Soziale Passagen 13, pp. 235–252.

Künkel, Jenny (2020): ‘Sex, Drugs & Corona’, in: Anderson, Sage / Blok, Gemma / Fabian, Louise (Eds.): Marginalization and space in times of COVID-19. https://narcotic.city/governing_wp/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Lockdown_Report.pdf (accessed: 11.04.2025), pp. 39–50.

Künkel, Jenny (2021): ‘Sexualpolitik als Experimentierfeld neuer Politikmodi – Zur Generalisierung von Viktimisierungsnarrativen im pandemischen Sexarbeitsdiskurs’, in: Sexuologie 28(1/2), pp. 107–115.

Künkel, Jenny (2025): Forderungen von Wohnungslosenaktivist*innen, online: https://protestinstitut.eu/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/WSZusammenfassung_Forderungen_Wohnungslosenaktivismus.pdf (accessed: 11.04.2025)

Nagel, Stephan (2022): ‘Selbsthilfe, Selbstorganisation und politische Mobilisierung wohnungsloser Menschen’, in: Widersprüche 165, pp. 67–80.

Sowa, Frank / Sellner, Nora / Tissot, Anna Xymena (2024): Lokale Hilfesysteme für wohnungslose Menschen im Wandel. Nürnberg: Ohm.

Valentina; Jose (2022): ‘Housing First selber machen’, in: Zeitschrift Luxemburg, online: https://zeitschrift-luxemburg.de/artikel/housing-first-selber-machen (accessed: 11.04.2025)